|

|

|

Today when we hear a piece of music we often notice it is associated with a story, or a programe as it is known more formally in the music community. Pieces which are associated with a programe are called, quite obviously, programmatic pieces. One can think of works such as Berlioz’s symphonie fantastic, and Beethoven’s pastoral symphony as examples of this form. So what exactly is a programmatic piece? It is roughly defined as a composition which reflects a story, event, or series of events within its music. I usually like to divide this large group into two: the programmatic pieces (compositions which have and extended, complex program, such as the symphonie fantastic), and the depictive pieces (compositions which have only a small programe, often only a couple of lines long, such as Beethoven’s Pastoral symphony). Why this separation you ask? I personally think that it is necessary for absolute clarity, as one would not deny that the listener engages in a different experience with each the genre, therefore it is necessary it bill them as different “forms” so to speak. But for something so prevalent in our modern music, the evolution of the programe, and compositions which involve, it was slow in coming, not becoming completely perfected until the Romantic Movement. Throughout history many composers did portray programmatic sensibilities in their music, these becoming landmarks in the genre culminating in the final creation of the romantic programe.

The Baroque era:

The main contribution of the baroque to music altogether was the evolution that the renaissance polyphony took among the imitative forms of the genre. Other breakthroughs included the continuing secularization of the arts; a practice which had first began to come into being in the renaissance, and was still taking effect in the baroque. But the secularization of music was still a relatively new concept, and it is for that reason that many of the works based upon the notion of a programe, if not an exact programe, would tend to be sacred works. There are a few compositions, such as Telemann’s Don Quixote, a pseudo-programmatic suite for strings, which were not sacred, but, as the recognition of the cantata as one of the main compositional forms would indicate, the bulk of the programmatic musical literature was sacred.

This being said, the programe itself was also in its infancy, examining Telemann’s Don Quixote, which was mentioned above, let us dissect its programe. The programe consisted of only a title and a single sentence or phrase which served as a subtitle to each of the movements of the suite, and thus was very simple in its nature. This characterizes the baroque programmatic works more than anything else, the simple programe. There was also an issue of the baroque musical and instrumental style, which was still evolving from the previous era’s noticeable emphasis on vocal music. The style itself tended to dominate the music, since it was very rigid, leaving little room for the programe to be suitably illustrated. This fact was one of the major holdbacks to programmatic music in the era, even though composers could make some works “stand out” so to speak, there wasn’t the ability to facilitate the vivid imagery which is demanded from a more complex notion of the programe. The Magic Flute: even in the first few bars the opera helped the development of the programe

The Classical era:

In the Classical era cultural, theoretical and technological differences clearly differentiated the musical style from all which had came before it, the focus on triadic and more or less consonant harmony and melody, and the invention of the piano just to name a few. The clearest indication of the advancement of the programe during the classical era could be observed within the walls of the theater. The genre now being called opera was quickly growing from its fledgling state in the Baroque era into a reputable musical genre and even later in the period to become the dominant genre in music, to the point where all composers who composed symphonic music would be obligated to try their hand at it (some more successfully than others mind you). The advancement of the programe was due to the ever growing need to represent the setting and mood through the music, and thus one can easily see that Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro and The Magic Flute have different types of music accompanying the play because of the different settings. This trend in opera later in history got to the point where the music was used to tell the story as much as the libretto. This technique is called through composed opera, and was first originated by the famous Richard Wagner.

Apart from the leaps which were facilitated by the popularity of opera, the Classical era still suffered from the what the baroque had also suffered: the Style was extremely rigid and representative of itself, and therefore allowed little ability to create and image on its own, as the images one must create in a programmatic piece are all very diverse and very complex. The harmonic basis of all the era was the triad, and little more. And amplifying this characteristic was the classicist notion that one should create a melodic line which is simplistic and tonal, if not completely triadic based. One can think of Mozart’s Non pui andre aria from The Marriage of Figaro. Its melody, even though beautiful, revolves around the dominant and mediant intervals while an arpeggio which begins on the tonic completes the harmony and the triad. It changes to different chords and subsequent arpeggios, and the melodic dominant-mediant line progresses with it. The second part of the melody is just a rhythmic arpeggiation of the tonic triad closing with a half-cadence which is followed by a complete Da capo repetition and finishes with an authentic cadence in the tonic key. This is merely a genius creating a textbook version of a melodic line. I sum, it was this characteristic which held the music from achieving the goals of the Romantic period.  A Scene from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro (thanks to sfopera.com)

The Romantic era:

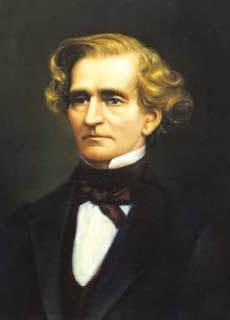

The final era of the development of programmatic music started off much like the classical era. The harmonic-melodic triad still reigned supreme and the old forms were still in wide use. Soon though, social changes began to erupt, and the composers found themselves pressing the limits of their current music theory. They found ways to embellish the all-to-rigid harmony of the previous era, such as the growing use of chromatic alterations within the melody of a composition. Also counterpoint, a subsection of harmony, experienced a movement to “break all the rules”. Claude Debussy (an impressionist at the end of the romantic period) in his Prelude to an afternoon in faun used both an early form of chromatic counterpoint (a distinctly early atonal concept), and parallel fifths and octaves by different orchestral instruments (the foremost “no-no” in tonal harmony) in order to expand the harmonic territory in which he could work. This did not cause the world to explode (as many eighteenth century theorists would have imagined) but rather in the hands of Debussy, a more than capable composer by all accounts, sounded the essence of Romanticism, “the social secularization of music” in the words of one theorist. It was on to this stage that Hector Berlioz, a composer and friend of personages like Rimsy-Korsakov and Alexander Borodin, stepped. His early life consisted mostly of failure, unfortunately enough. His father fist wanted him to attend Medical School, but many accounts say he fainted upon seeing a corpse for the first time. By the time he studied music in the Paris conservatory, he was not very sure of himself, but did turn out to be a relatively good composer. His most noted composition, the symphonie fantastic (as I mentioned above), was what most scholars would most likely point to as the first truly programmatic composition; It had a complete and lengthy programe which depicted a series of events autobiographical to Berlioz’s life. Hector Berlioz is accredited with theFirst truly programmatic composition

Many more followed, both depictive and programmatic, from Borodin’s in the steppes of central Asia, to the Ring cycle of Wagner. The new music was in full force and could comment on any and all things, from social conflicts to personal issues, and the composer was for the most part expected to be more expressive as an artist than was previously necessary. Many accepted this new challenge and worked to create for themselves. In a sense the programe became as small point for a large revolution in musical thought.

And Today:

Earlier this year I attended the “world premier” of a composition entitled Fallen Heroes: A secular Oratorio. It had a programe which was literally ten pages long, listing the composer’s “artistic influences” and also painstakingly analyzing the mediocre poetry which this man was now setting to music. The music was typical of the academic professor who wrote it, and the pamphlet which came with the tickets would have in truth been better off without it. But the notable thing is that this genre is still in practice, even by the academics, who always want to stay on the cutting edge. This type of expression in music is universal, whether it is through the beauty brilliance of Rimsy-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, or the tedium and unsettling sounds of Fallen Heroes. It will always stay this way also, because the lure of art as a form of expression is too great for the composer to resist, and why should we? We all yearn for a place to express ourselves, explicitly, for all to hear. This is our best place as the creators of music. Not abstract, but obvious. This is our wish, that what we create with our emotions and ourselves will be enticing to all who hear it. And for this there is no better medium than the programe.

The contents, views and opinions in this article are those of its author.

|

|

|

|

|

|